Nonfiction comics-format coverage of CAAMFEST 2016, the Center for Asian American Media’s annual film festival. Co-written by me and Minnie Phan; illustrated by Minnie. Originally commissioned by and serialized at Colorlines, March 23-28 2016. Text transcript at the bottom of the page.

Text transcript follows.

Colorlines at CAAMFest 2016, Part 1 Script

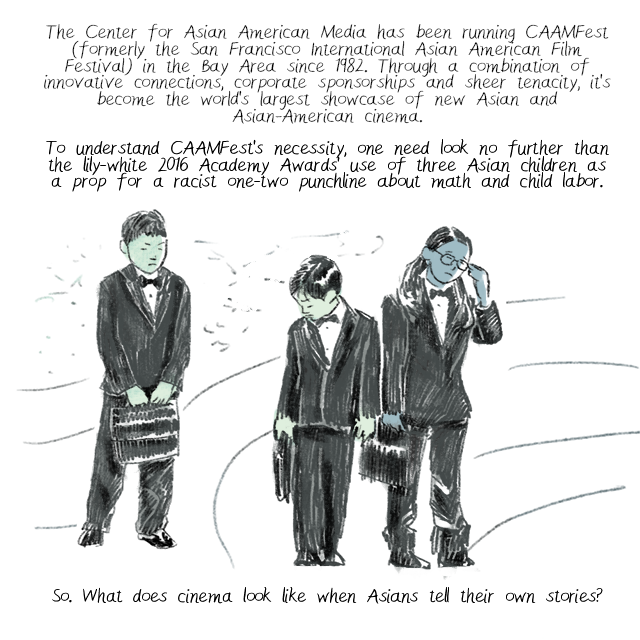

The Center for Asian American Film has been running CAAMFest (formerly the San Francisco International Asian American Film Festival) in the Bay Area since 1982. Through a combination of innovative connections, corporate sponsorships and sheer tenacity, it’s become the world’s largest showcase of new Asian and Asian-American cinema.

To understand CAAMFest’s necessity, one need look no further than the lily-white 2016 Academy Awards’ use of three Asian children as a prop for a racist one-two punch line about math and child labor

So. What does cinema look like when Asians tell their own stories?

Panel: “A Brave New Digital World”

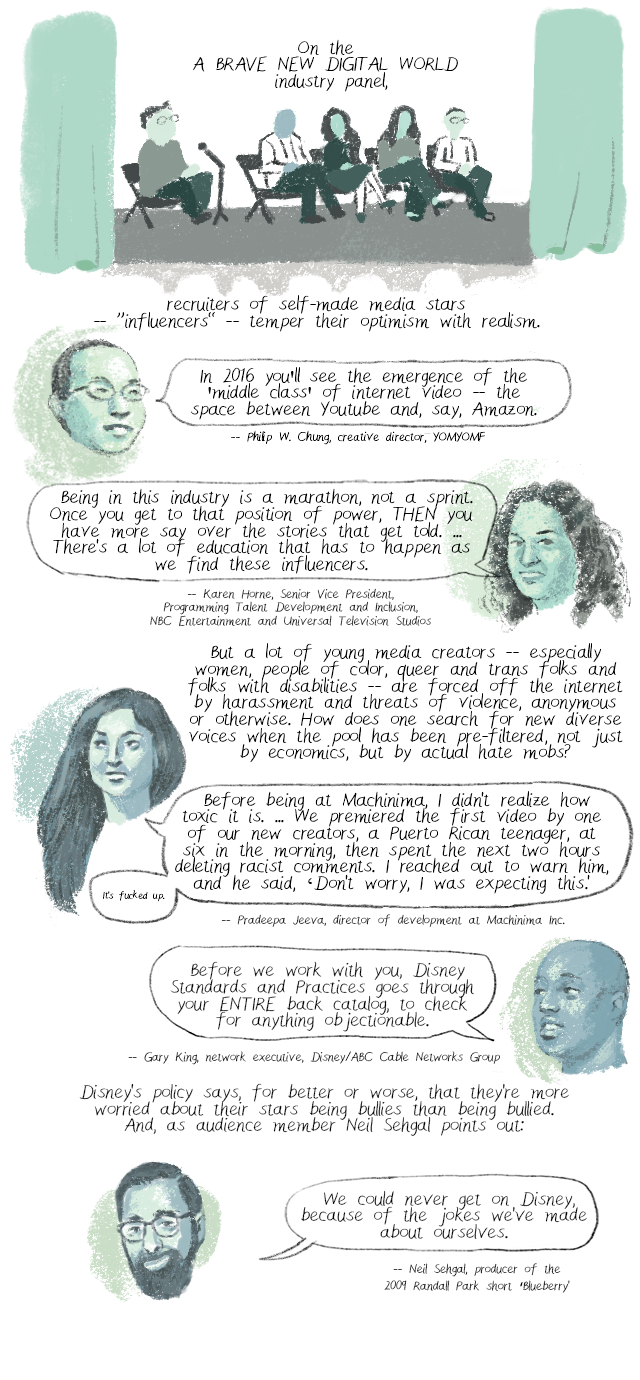

On the “A Brave New Digital World” industry panel, recruiters of self-made media stars—“influencers”—temper their optimism with realism.

“In 2016 you’ll see the emergence of the ‘middle class’ of Internet video —the space between YouTube and, say, Amazon,” said Philip W. Chung, creative director of YOMYOMF.

“Being in this industry is a marathon, not a sprint. Once you get to that position of power, then you have more say over the stories that get told. … There’s a lot of education that has to happen as we find these influencers,” said Karen Horne, senior vice President of Programming Talent Development and Inclusion and NBC Entertainment and Universal Television Studios.

But a lot of young media creators—especially women, people of color, queer and trans folks and folks with disabilities—are forced off the Internet by harassment and threats of violence, anonymopus or otherwise. How does one search for new diverse voices when the pool has been pre-filtered, not just by economics, but by actual hate mobs?

“Before being at Machinima, I didn’t realize how toxic it is. …We premiered the first video by one of our new creators, a Puerto Rican teenager, at six in the morning, then spent the next two hours deleting racist comments. I reached out to warn him, and he said, ‘Don’t worry, I was expecting this,’” said Pradeepa Jeeva, director of development at Machinima Inc. “It’s fucked up.”

“Before we work with you, Disney Standards and Practices goes through your entire back catalog, to check for anything objectionable,” said Gary King, network executive, Disney/ABC Cable Networks Group.

Disney’s policy says, for better or worse, that they’re more worried

about their stars being bullies than being bullied. And, as audience

member Neil Sehgal, producer of the 2009 Randall Park short “Blueberry”

points out: “We could never get on Disney, because of the jokes we’ve made about ourselves.”

Film: “Colma the Musical”

Of course, artists don’t need permission. CAAMFest 2016 marked the ten-year anniversary of the cult Bay Area classic “Colma the Musical,” made in 2006 for $1000.

Written by, composed by and starring H.P. Mendoza, and based on his experiences as a young gay Filipino growing up in (and yearning to get out of) the titular mall-riddled Bay Area town, “Colma” tells a universal story through uncelebrated people.

Minnie says: “I went into this live sing along not knowing any of the words but, as someone who grew up

queer

and Vietnamese in the South Bay, I knew all the feelings.” Minnie had

no idea what she was singing, but she was singing it loudly.

Film: “The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift”

On the opposite end of the spectrum from “Colma,” CAAMFest 2016 also celebrated the 10-year anniversary of: “The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift.”

“We’re gonna get a little misogynistic tonight, is that all right?” asked the CAAMFest emcee. “NO,” said the audience.

“Tokyo Drift” is, or was going to be, a movie about a White kid who

breaks the law so much that he gets a free trip to Japan. To solve

issues with the screenplay, director Justin Lin created the character

‘Han Seoul-Oh’

(whose last name isn’t said in the film). Bad puns aside: Han is the best.

Han is a genuinely cool, charismatic character whom you love seeing

on screen, and he’s neither stereotypically Asian nor “happens to be”

Asian. (As a result, it’s hard to imagine him surviving a focus group.)

His immediate fan-favorite status, and continuance on into the sequels,

speaks volumes about how behind-the-camera representation can translate

into

successes both artistic and fiscal.

Says Minnie: “Seeing this movie 10 years ago in the theater, my cousins freaked out about every new car that came on screen. This movie is surprisingly documentarian for me! Like a tour of every hot-rod-and-bikini-babe poster in my friends’ brothers’ bedrooms. It’s… unclear how far we’ve come.”

Adds Channing: “I’m reminded of the late Roger Ebert in at Sundance

2002, roasting a fellow White audience member for telling Asians how to

“represent” themselves. This movie—this very silly movie—is

the one Lin set out to make.

One last bit of trivia from the pre-show panel: Argentina-born, Australia-raised actor Leonardo Nam says he based his bleach-blonde Yakuza character on the neo-Nazi hipsters he’d seen while shooting an indie film in Berlin. Huh!

Stay tuned for the part 2 of Colorlines @ CAAMFEST2016!

Colorlines at CAAMFest 2016, Part 2 Script

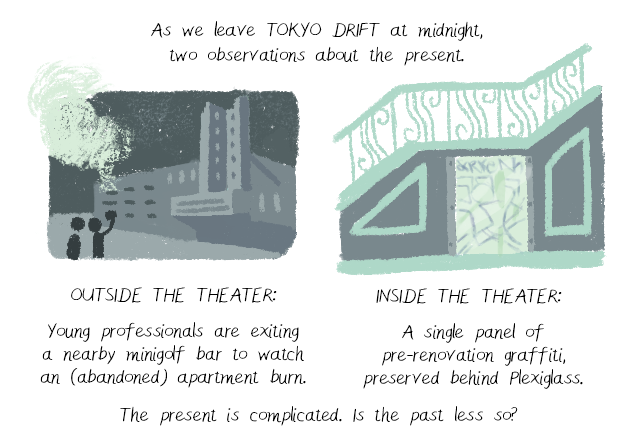

As we leave “Tokyo Drift” at midnight, two observations about the present. Outside the theater, young professionals are exiting a nearby minigolf bar to watch an (abandoned) apartment burn. Inside the theater is a single panel of pre-renovation graffiti, preserved behind Plexiglass.

The present is complicated. Is the past less so?

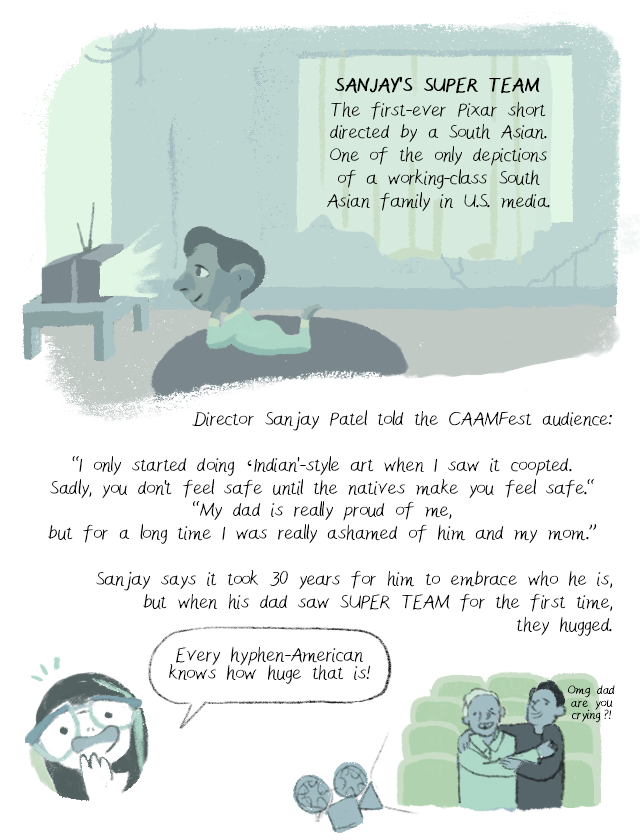

Film: “Sanjay’s Super Team”

It’s the first-ever Pixar short directed by a South Asian and one of the only depictions of a working- class South Asian family in U.S. media. Director Sanjay Patel told the CAAMFest audience: ”I only started doing ‘Indian’-style art when I saw it coopted. Sadly, you don’t feel safe until the natives make you feel safe.”

He added ”My dad is really proud of me, but for a long time I was really ashamed of him and my mom.“ Sanjay says it took 30 years for him to embrace who he is,mbut when his dad saw “Super Team” for the first time, they hugged.

Says Minnie: Every hyphen-American knows how huge that is!

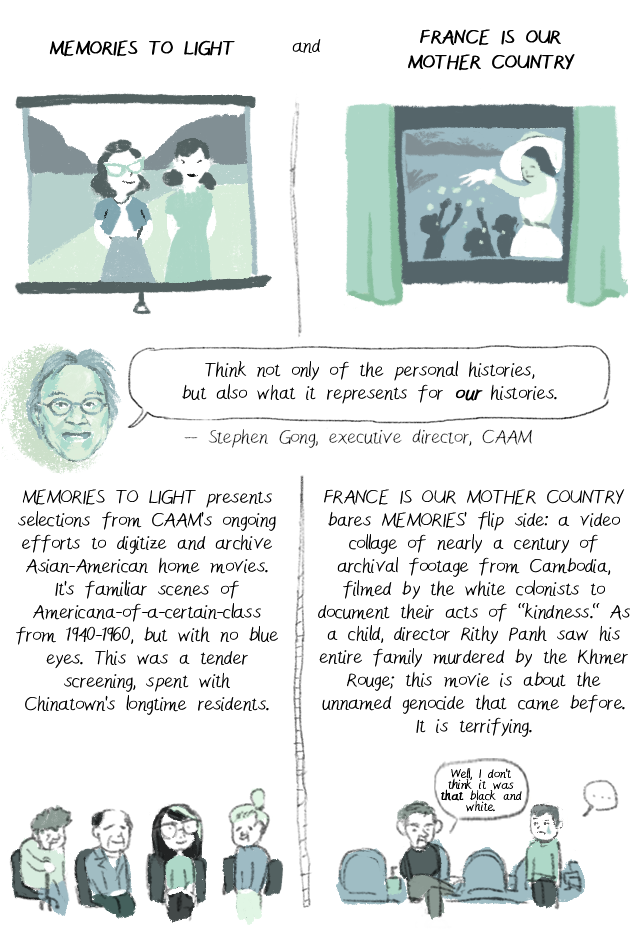

Films: “Memories to Light” and “France is Our Mother Country”

Think not only of the personal histories, but also what it represents for our histories. said Stephen Gong, executive director, CAAM

“Memories to Light” presents selections from CAAM’s ongoing efforts to digitize and archive Asian-American home movies. It’s familiar scenes of Americana-of-a-certain-class from 1940-1960, but with no blue eyes. This was a tender screening, spent with Chinatown’s longtime residents.

“France is Our Mother Country” bares Memories’ flip side: a video collage of nearly century of archival footage from Cambodia, filmed by the White colonists to document their acts of ”kindness.” As a child, director Rithy Panh saw his entire family murdered by the Khmer Rouge; this movie is about the unnamed genocide that came before. It is terrifying.

An old White guy in the audience says, ”Well I don’t think it was that black and white.” Channing shoots him a dirty look.

Interview: Nikki H.

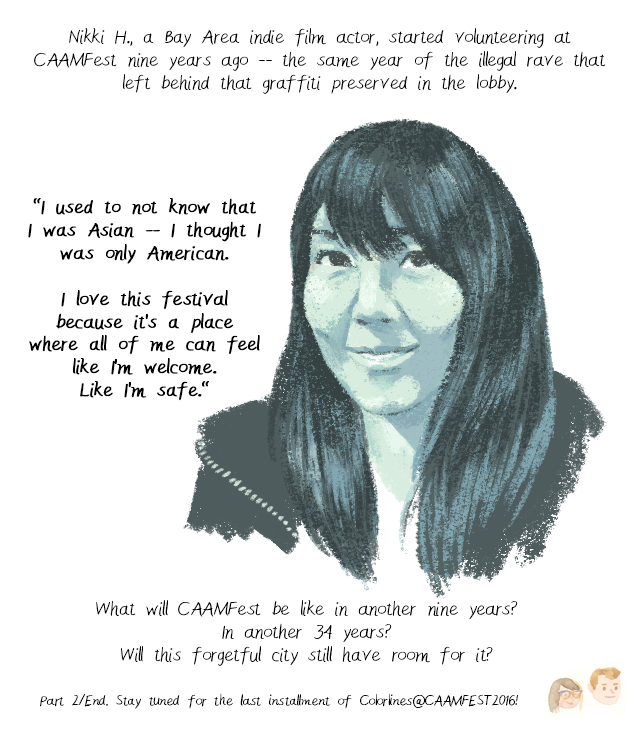

Nikki H., a Bay Area indie film actor, started volunteering at CAAMFest nine years ago—the same year of the illegal rave that left behind that graffiti preserved in the lobby.

Nikki said, “I used to not know that I was Asian—I thought I was only American. I love this festival because it’s a place where all of me can feel like I’m welcome. Like I’m safe.”

What will CAAMFest be like in another nine years? In another 34 years? Will this forgetful city still have room for it?

Stay tuned for the last installment of Colorlines@CAAMFEST2016!

Colorlines at CAAMFest 2016, Part 3 Script

It’s the last weekend of CAAMFest! We weren’t able to experience all of it, but we’ve seen:

– five documentaries

– four narrative features

– two shorts programs

– two panels

–

and before every screening, Justin Lin’s head telling the air to the

left of to the camera lens to check out a corporate sponsor’s website.*

* This probably doesn’t bother anyone who’s seen the pre-roll fewer than 13 times.

Film: “Breathin’: The Eddie Zheng Story”

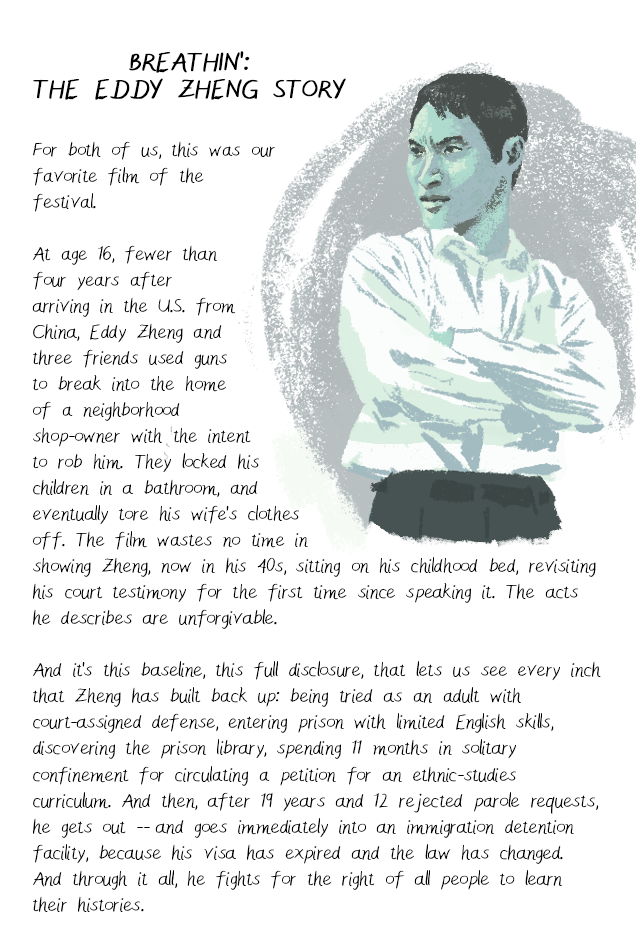

For both of us, this was our favorite film of the festival. At age 16, fewer than four years after arriving in the U.S. from China, Eddie Zheng and three friends used guns to break into the home of a neighborhood shop-owner, locking his children in a bathroom and eventually ripping her clothes off. The film wastes no time in showing Zheng, now in his 40s, sitting on his childhood bed, revisiting his court testimony for the first time since speaking it. The acts he describes are unforgivable.

And it’s this baseline, this full disclosure, that lets us see every inch that Zheng has built back up: being tried as an adult with court-assigned defense, entering prison with limited English skills, discovering the prison library, spending 11 months in solitary confinement for circulating a petition for an ethnic-studies curriculum. And then, after 19 years and 12 rejected parole requests, he gets out—and goes immediately into an immigration detention facility, because his visa has expired and the law has changed. And through it all, he fights for the right of all people to learn their histories.

“Breathin’” could have settled for “inspirational”: guy goes to jail, turns his life around, cue credits. Instead, it holds all players accountable, for everything. We hear Zheng’s mother admit to claiming that he was off at college instead of serving time in prison. We see her refuse to apologize for not asking her father to pay for an attorney. We see his sister say that they thought jail “might be good for him.” And we spend time with the voice of victims: One of the shop-owner’s children lays out every reason to keep him in prison forever, to deport him, to “let him make a new life anywhere but here.”

We also see Zheng open his heart for rooms full of men both before and after getting his freedom. We watch him works a bullhorn at rallies, demanding Asian solidarity with the African-American community. We see his girlfriend teasingly objectify his biceps. We get to see Zheng be funny, loving, distant, terrifying, and scared. We see him be a son and a father. As Zheng’s former cell mate asks, “If Eddie isn’t reformed, who is?” And this is a movie about how reformation is not an erasure of the past. Eddie Zheng, as rendered on screen by director Ben Wang and a decade’s worth of filming, may be the most fully human Asian man on a U.S. movie screen in recent memory.

Postscript: during the movie, we both wondered who was letting their toddler wander around the theater. But we both figured it out when she trundled up to Zheng’s giant face on the screen and yelled “Daddy!”

Film: “Painted Nails”

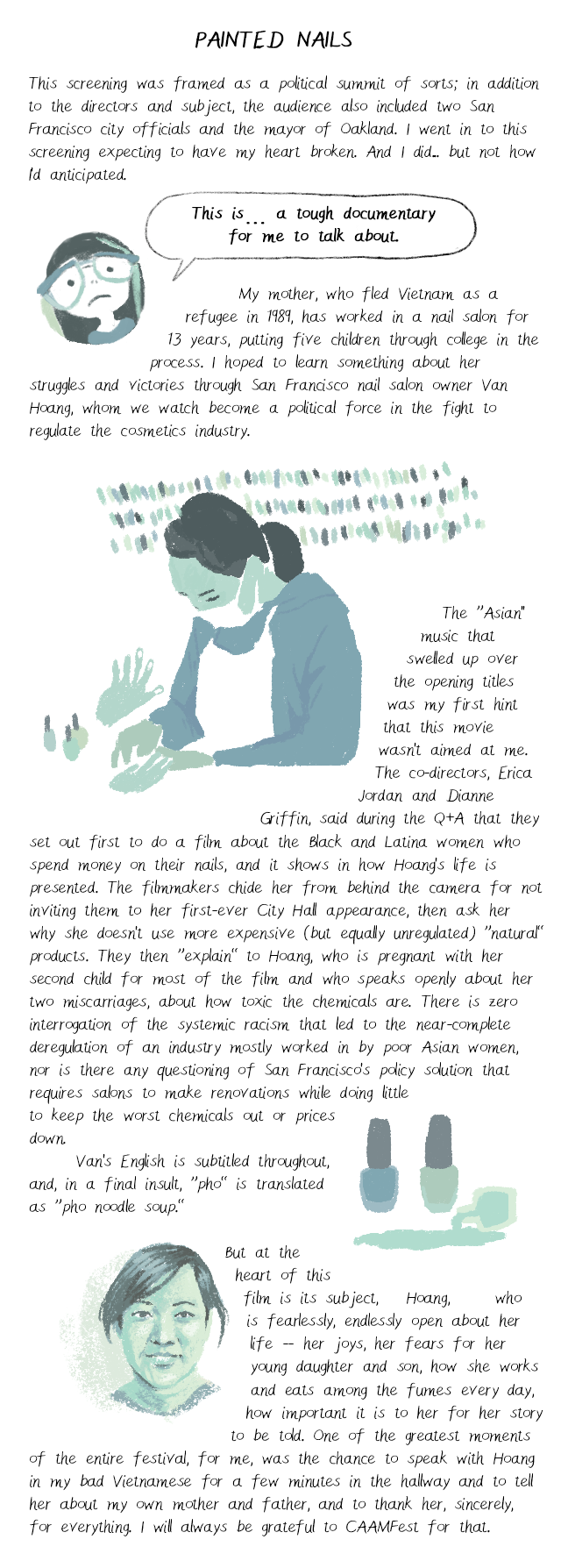

This screening was framed as a political summit of sorts; in addition to the directors and subject, the audience also included two San Francisco city officials and the mayor of Oakland. I went in to this screening expecting to have my heart broken. And I did… but not how I’d anticipated.

“This is… a tough documentary for me to talk about,” said Minnie.

“My mother, who fled Vietnam as a refugee in 1989, has worked in a nail salon for 13 years, putting five children through college in the process. I hoped to learn something about her struggles and victories through San Francisco nail salon owner Van Hoang, whom we watch become a political force in the fight to regulate the cosmetics industry.

The ‘Asian’ music that swelled up over the opening titles was my first hint that this movie wasn’t aimed at me. The co-directors, Erica Jordan and Dianne Griffin, said during the Q+A that they set out first to do a film about the Black and Latina women who spend money on their nails, and it shows in how Hoang’s life is presented. The filmmakers chide her from behind the camera for not inviting them to her first-ever City Hall appearance, then ask her why she doesn’t use more expensive (but equally unregulated) “natural” products. They then ‘explain’ to Hoang, who is pregnant with her second child for most of the film and who speaks openly about her two miscarriages, about how toxic the chemicals are. There is zero interrogation of the systemic racism that led to the near-complete deregulation of an industry mostly worked in by poor Asian women, nor is there any questioning of San Francisco’s policy solution that requires salons to make renovations while doing little to keep the worst chemicals out or prices down.

Hoang’s English is subtitled throughout, and, in a final insult, “pho” is translated as “pho noodle soup.”

But at the heart of this film is its subject, Hoang, who is fearlessly, endlessly open about her life —her joys, her fears for her young daughter and son, how she works and eats among the fumes every day, how important it is to her for her story to be told. One of the greatest moments of the entire festival, for me, was the chance to speak with Hoang in my bad Vietnamese for a few minutes in the hallway and to tell her about my own mother and father, and to thank her, sincerely, for everything. I will always be grateful to CAAMFest for that.”

Shorts: Muslim Youth Voices

These quickly made, gorgeously produced shorts were created in CAAM’s weeklong Muslim Youth Voices workshops in Somali communities in Minneapolis and Philadelphia, with the guidance of filmmaker Musa Syeed. This is some of the festival’s most innovative cross-community work—an expansion, rather than a contraction, of who should benefit from CAAM’s platform and influence. And, admirable organizational missions aside:

“I loved this program,” said Channing. “Scenes that will stay with me long after the festival: a zombie with hijab and braces, transformed by sugary school lunch (‘Food For Thought,’ dir. Rizky Chandra); a young woman reciting her poem ‘If I Were A Black Man’ (‘Imagination,’ dir. Roodo Abdikadir); two kids using a time machine that looks a lot like a microwave, then introducing themselves as ‘You! From the future!’ ’And Ted! … uh, from the future!’ (‘Friends In Time,’ dirs. Gallant Abidin and Niedal Jalil)

As Minneapolis spoken-word artist Sisco said during the Q+A, ‘While we were filming, people from the neighborhood would come up and ask us what happened because we don’t get cameras in our neighborhood unless something bad happened.; When’s the last time you saw a Muslim kid on TV just being a goofball?’”

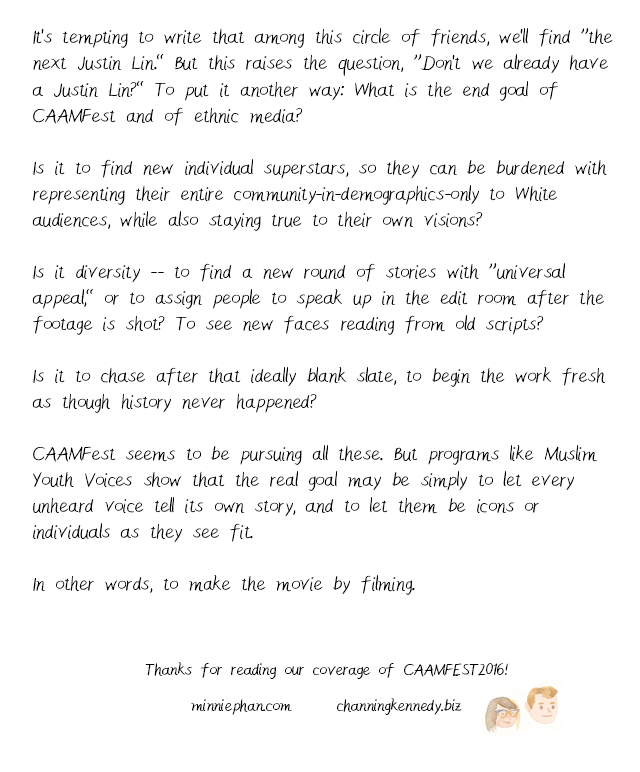

Image: a young woman in hijab walking away from TV said, “You know what? I don’t even need you. I can share my own story.” (“Screened,” dir. Iqbal Maxamed).

It’s tempting to write that among this circle of friends, we’ll find “the next Justin Lin.” But this raises the question, “Don’t we already have a Justin Lin?” To put it another way: What is the end goal of CAAMFest and of ethnic media? Is it to find new individual superstars, so they can be burdened with representing their entire community-in-demographics-only to White audiences, while (somehow) also staying true to their own visions? Is it diversity—to find a new round of stories with “universal appeal,” or to assign people to speak up in the edit room after the footage is shot? To see new faces reading from old scripts? Is it to chase after that ideally blank slate, to begin the work fresh as though history never happened?

CAAMFest seems to be pursuing all these. But programs like Muslim Youth Voices show that the real goal may be simply to let every unheard voice tell its own story, and to let them be icons or individuals as they see fit.In other words, to make the movie by filming.

Thanks for reading our coverage of CAAMFEST2016!

[end of transcript]